Sessions 11 - 13

Sessions 11-13

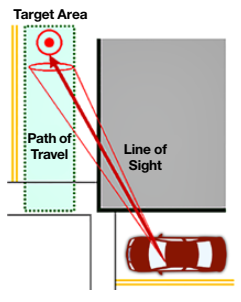

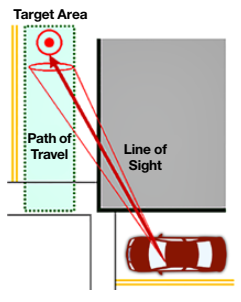

Searching Intended Path of Travel

In a residential area, or, if ready, on roads with light traffic, continue working on basic visual skills, negotiating curves, and right and left turns. Practice judging space in seconds, identifying a target, and searching the target area and target path. Ask your teen to comment prior to changing speed or position.

Novice drivers have the tendency to monitor the road immediately in front of the vehicle. The target is a fixed object that is located 12-20 seconds ahead of the vehicle, in the center of the path of travel, and is what the driver steers toward. It can be a car a block ahead, a traffic signal, the crest of a hill, etc. To practice this skill, use commentary driving for two to three minutes, and have your teen identify targets. Having a target helps the new driver to:

- visualize the space the vehicle will be occupying;

- look far ahead of the vehicle and begin a search to identify risks;

- improve steering accuracy.

The SEEiT system: Search, Evaluate, and Execute in Time, is a simple space management system your teen can use to minimize or control driving risks. When Searching the path of travel, the new driver should look for open, changing, and closed areas. Examples of a closed area would be a stop sign, stopped traffic, red light, etc. Examples of a changing area would be a car pulling out of a driveway, a left-turning vehicle, a bicyclist, etc. Ask your teen to use commentary driving to identify and Evaluate changing or closed space when approaching intersections, and then Execute a speed or position change in Time to reduce risk.

The need to adjust following space occurs when speed or road conditions change. A simple way to measure following space is in intervals of seconds. You can steer around the risk in much less time than you can brake and stop to avoid colliding into the risk. The distance for steering is much shorter than the distance for stopping. Coach the new driver to look for open space, or an “escape route,” not at what he or she is trying to avoid. We steer in the direction we look.

A two-second interval provides the driver time to steer out of problem situations at posted speeds on a dry surface and brake out of problems at speeds under 35 mph.

A three-second interval provides the driver time to steer out of problem areas and to brake out of problems at speeds under 45 mph on a dry surface.

A four-second interval provides the driver time to steer or brake out of problems at speeds under 65 mph on a dry surface.

Judging Space in Seconds

When traveling at 25 to 30 mph, looking 12 to 15 seconds ahead translates into about one city block. This is the targeting area the driver must monitor. Stopping zones are 4 to 8 seconds ahead, and following distance is 3 to 4 seconds. To calculate space in seconds, have the new driver select a fixed target, count one-one thousand, two-one thousand, etc., until the driver reaches the object. Ask your teen to practice judging space in seconds at different speeds, and discuss escape routes and stopping distances.

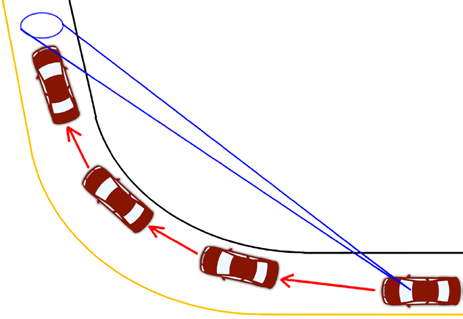

Coaching Your Teen to Control a Vehicle through a Curve

- On approach, position the vehicle in the lane to try to establish a sightline to the apex and exit of the curve. Observe warning sign speed, which is calculated on the angle and bank of the curve.

- Reduce speed before entering the curve, and slowly lighten the pressure on the brake until reaching the apex point (where the car is closest to the inside of the curve line). At the apex or exit point, coach the new driver to apply light acceleration to pull the car out of the curve.

The vehicle’s speed and load, and the sharpness and bank of the curve affect vehicle control. Traction loss when entering a curve is often caused by excessive speed, braking, or steering. Front tire traction loss is referred to as “under-steer,” and is more likely to occur in front-wheel drive vehicles. It causes the vehicle to “plow” straight ahead and the vehicle will not respond to steering input. “Over-steer” is when there is traction loss by the rear tires and occurs more often in vehicles with rear-wheel drive. It causes the rear of the vehicle to slide from one side to the other and occurs when the rear tires try to lead (fishtailing).

Vehicle balance refers to the distribution of the vehicle’s weight on all four tires. Ideal balance and tire patch size is only reached when the vehicle is motionless. As soon as acceleration, deceleration, cornering, or a combination of these actions occurs, vehicle balance and weight on the tires change. However, if the vehicle is traveling at a constant speed, and the suspension is set on center, steering and traction control is considered to be in balance.

Changing Vehicle Balance from Side to Side (Roll)

Sudden steering, accelerating, braking, or road design can affect a vehicle’s side-to-side balance. Example: steering to the right shifts the vehicle weight to the left.

Changing Vehicle Balance from Front to Rear (Backward Pitch)

When acceleration is applied, weight or center of mass is transferred toward the rear of the vehicle. More rapid acceleration results in greater weight transfer and reduced front tire traction.

Changing Vehicle Balance from Rear to Front (Forward Pitch)

When brakes are applied, weight or center of mass is transferred toward the front of the vehicle. If braking is hard, there is a noticeable drop of the hood and reduced rear tire traction.

Changing the Vehicle’s Rear Load to the Right or Left (Yaw)

Sudden steering, braking, slippery road surface or a right or left elevation of the highway can affect rear vehicle balance and result in the loss of rear tire traction. If a rear tire has less traction than the corresponding front tire, that tire will begin to slide sideways towards the front tire. This spinning action is called vehicle yaw.